oxford 8-9 december: of robots, men and minds

robots, men and minds – that was the title of one of ludwig von bertalanffy’s books in the sixties. toru nishigaki from the university of tokyo talked about the same topic when holding the keynote at the information ethics conference organised by the japanese uehiro foundation on ethics and education and the carnegie council of ethics in international affairs at the oxford uehiro centre for practical ethics on 8 and 9 december.

is a society of cohabitation with robots possible? toru agreed with the findings in western literature that traditional japanese animism opposes the western idea of the hierarchy of existence. according to the animistic world view everything has its own spirit and this holds for artifacts too. they are based on an equal footing, while in western hierarchical thinking they are ranked even below animals.

though toru does not like to support such an anthropocentric position, he addresses the concern that japanese thinking “does not necessarily offer a safeguard against a cyborg and/or mechanization of human thinking.” japanese people even seem to be accustomed to living in mechanical clock-wise rhythm. for the future toru foresees a possible development of human minds coming closer and closer to robots while robots never will exhibit a mind comparable with human mind.

that’s exactly that scenario that ludwig von bertalanffy never stopped warning against. and that scenario is not due to animistic thinking but to capitalism-driven, techno-oriented development of society.

in my view, animism can be taken cum grano salis. there is something in common to living beings and artifacts. but that does not mean that there is no difference as to their existence. artifacts, technology, computer technology are not made by themselves, autonomously; they are created by us humans and they belong to nature mediated via our productive forces that are, in the last resort, productive forces of nature itself. though robots belong to nature in that respect, this does not mean they do not make any difference. on the contrary, they have the potential for being instrumental (in the sense of ivan illich’s convivial tools) or detrimental as well (and nowadays they can be as detrimental as to put the future of humanity at stake).

thus hierarchical thinking, on the other hand, can also be taken cum grano salis like in hierarchical systems thinking. it does not need to lead to what is called anthropocentrism. since technology as human product enjoys a kind of relative autonomy, it has to be taken care of in a permanent process of technology assessment and technology design.

it is only then that we can state that harmony should not be sought in a mechanical sense. what is to be sought is “unity through diversity” – a dialectical relationship.

in the center toru nishigaki. on the right rafael capurro. on the left tadashi takenouchi (photo: fumio shimpo).

again toru nishigaki on the left, bill dutton on the right. in the background me giving my lecture on ethics of sustainability in the perspective of complexity. (photo: fumio shimpo).

on the right johannes britz (photo: hisateru onozuka).

a view of st. cross college where the conference took place (photo: fumio shimpo).

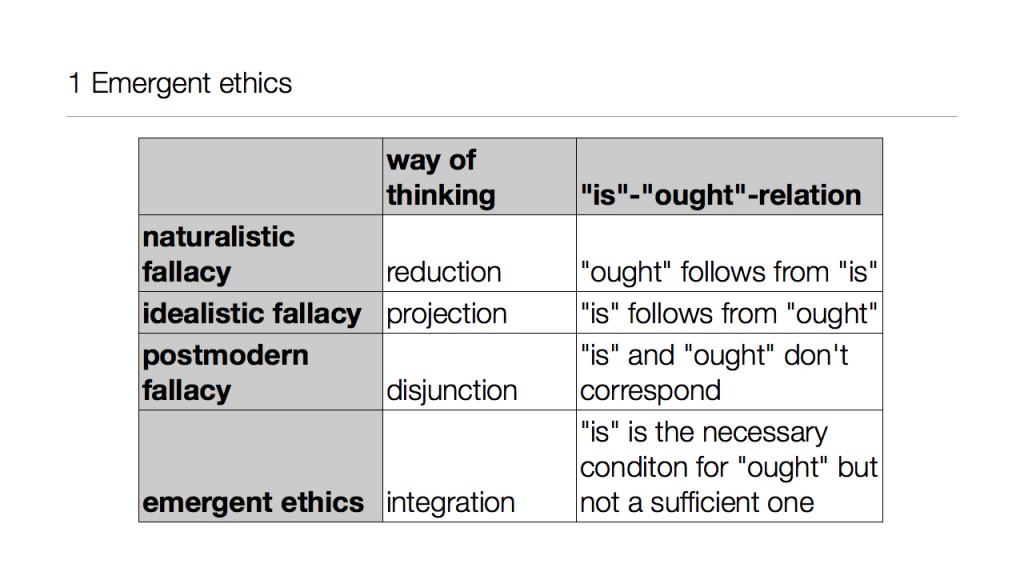

in my talk i introduced the meta-ethical standpoint of “emergent ethics”. that is deemed the dialectical solution of the is-ought problem. morals and values are not an idealistic given nor are they a materialistic ingredient of our world. they rather develop historically, based upon, but not determined by, these very historical circumstances – they emerge.

the slide in question from my talk.